Nearly a month before the United States started implementing control measures, I had an awaking to the escalating pandemic when I landed in Quito, Ecuador. I was immediately quarantined to complete a coronavirus test. It was February 29th, 2020, and the small South American nation had only one confirmed case of the virus at the time, a man who arrived on an international flight from Madrid.

On February 29th, 2020 the United States was still operating a full panel of flights to and from the European continent, and social distancing was not yet in the public lexicon.

A nation of immense pride and socialized medicine, Ecuador was not wasting any time in its coronavirus preparations. Impressively, while the U.S. bungled tests that took days to process, I was given a coronavirus test on arrival that returned results in less than 12 hours.

I knew things were about to get interesting the second I stepped on the escalator entering the arrivals hall at Quito Mariscal Sucre International Airport last month. Health officials were standing at the bottom waiting for me out of some Deja Vu dream, decked out in head-to-toe hospital gowns and industrial-grade respirator masks, aiming thermal guns at the group of passengers arriving from Lima.

Ironically, because I was seated in the first row of the flight, they didn’t actually hit me with one of their thermal eyeballs; I came down the stairs before they were ready.

It didn’t matter though, as I had arrived after connecting from Brazil, another country that had a solitary case of the novel coronavirus at that time. I was pulled aside with anyone else who had breathed outdoor air in any part of the world where the bug had thus far been found.

It was uniquely bad timing, as I had an elevated temperature after spending the previous 10 days at Brazil’s famed Carnaval street parties. I hadn’t slept normally for two weeks and my body was pissed. I did not, however, have any strain of coronavirus, and I had no symptoms indicating otherwise; no sneeze, no cough, no congestion or runny nose or headache. Just running a degree or two hot.

I figured there would be some hassle, but sitting with a thermometer sticking out of my armpit I couldn’t possibly have imagined exactly what I was in for. The United States, after all, had not imposed any formal requirements to test incoming international passengers, despite confirming hundreds of cases by that date.

After repeatedly probing my armpit and face for about two hours, five of the six medical professionals at the Ministry of Public Health’s airport checkpoint agreed that I was asymptomatic and should be sent through with a prescription for paracetamol. But one tall man had another idea; I was going to be taken to a hospital in an ambulance and administered a coronavirus test.

Quarantined To Complete a Coronavirus Test

At that moment a mask was placed over my mouth. A photographer from the Associated Press asked if she could take my photograph. I was taken to a room in the back office of the airport health clinic and told to wait. My luggage would be brought to me later, I was told. Thankfully, I had already taken back my stamped passport.

An hour or so later an ambulance arrived at the airside exit from the immigration hall. Out stepped three men in what looked like spacesuits, full personal protective equipment, the kind now unavailable to many U.S. first responders, dispatched to whisk me off. I was strapped to a stretcher. The ambulance darted off the airport tarmac and onto the mountain roads to Quito at maximum speed, sirens blaring, steam-horn barking at any non-yielding civilian.

Me in my ambulatory airport shuttle.

Rocking back and forth as the ambulance aggressively navigated hairpin turns, I was asked questions. Where was I from (New York), how long had I been ill (not at all), when did I notice symptoms (I didn’t feel like I had any symptoms). Either due to elapsed time or to the nauseating purge-inducing ambulance ride, the paramedics onboard were unable to reproduce the fever that had snared me at the airport.

That fever never would return, but at this point the locus of control extended far beyond the trained professionals in whose care I found myself captive. The levers of Ecuador’s greater public health apparatus had been invoked. I couldn’t help but feel anxious. I was an international alien drifting along the whims of raw public health policy – uncharted territory for everyone involved.

I had called the embassy when I was at the airport, to let them know that I was being taken in for suspected coronavirus. Again I called to inform the on duty officer, Kevin, of my movements.

“We’ve never quite dealt with anything like this,” he said. “They are a sovereign nation, so they have their own procedures and they think you have coronavirus. We will keep in touch.”

As I was wheeled out of the stretcher and rushed into the emergency department at Hospital Provincial General Pablo Arturo Suarez, I struggled to fend off a chilling thought. What if no-one was actually in charge of my situation. What if I was to be stowed away, a guinea pig and indefinite suspect, subject to confinement until the small Andean nation acquired the resources to manage me. They couldn’t possibly have a coronavirus test, I thought. In the U.S. hardly anyone could obtain one.

At The Hospital – Isolation

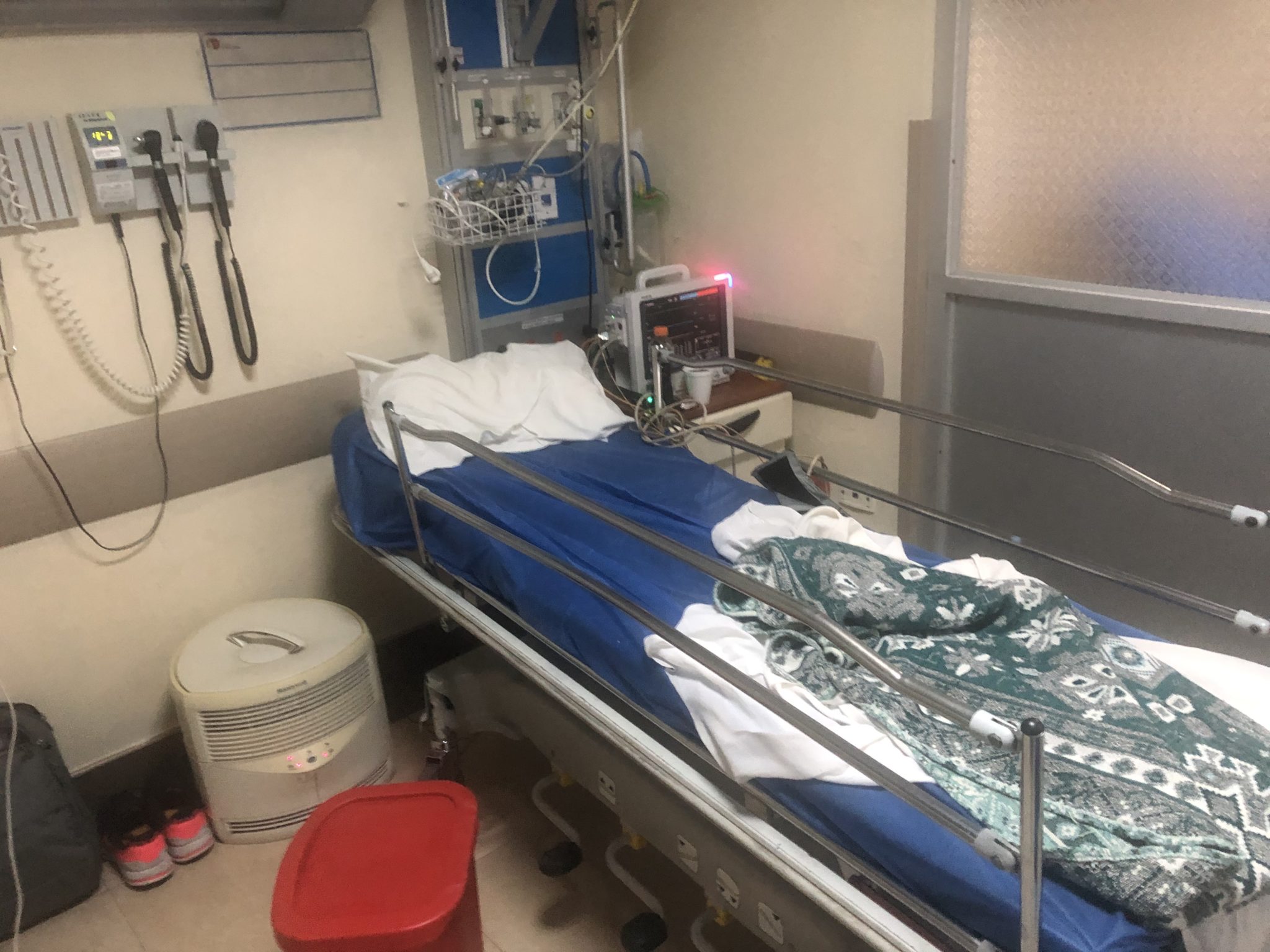

I was placed in the lone isolation room in the very corner of the hospital’s emergency department. All the other patients were separated by full-height curtains. There was a single open window near the top of the room and a single florescent light fixture to stare at for entertainment.

Before I could get a grasp on my surroundings one of the paramedics grabbed my fist and shoved an I.V. into my right arm. It was, re-markedly at age 29, the first time I’d experienced such a thing. My back muscles spasm-ed violently in pain as I felt the metal spear surge into my cephalic vein. Moments later, I was nearly sedated when a cool rush of paracetamol was unleashed into my arm.

On the other side of the bed a different paramedic unwrapped bundles of wires. An EKG was attached, a thermometer glued semi-permanently under my left armpit. Outside it started to pour rain. Each time the opaque door slid open I caught glimpses of wide-eyed nurses and physicians peering at my predicament from across the hall. My senses overwhelmed, I drifted into an intravenously induced slumber, adrift in a sea of supranational chaos.

When I finally awoke hours later I was alone and it was dark outside. The machine feeding my intravenous fluid had started beeping, as had the EKG monitor on the other side of the bed. I had to pee, but it wasn’t clear how that might happen. There was no one outside the door as far as I could tell or hear. I yelled for help in Spanish for about 15 minutes, but no one came. Seeking respite of silence, I instructed myself on operation of the IV monitor and EKG machine, which some help from Google. I fixed them both so that they would stop beeping, and drifted off to sleep again.

Lockdown

Some time later I awoke to the giant door panel sliding open. A woman in head-to-toe protective equipment walked in, a large plastic nose-cone protruding from her face. With her, she carried an enormous X-ray arm wrapped in radioactive caution tape. She approached my bedside slowly as she produced the longest cotton swab I’d ever seen in my life. No less than 18 inches end-to-end, I watched in horror as the woman silently navigated the swab toward my head, which was motionless, still sedate from my heavily medicated arrival. The end of the swab, my coronavirus test, though I didn’t know it at the time, dove into my left nostril seemingly infinitely. I gagged, sending the swab flying across the room. That was it.

Alarmed and still desperately unaware of what was happening, I let out a howl. “Noooo! No se puede molestarme! No lo consento!!!!”

I wagged my finger at the plastic nosecone, and scrambled to pick up my cell phone and redial the Quito Embassy. I shouted repeatedly in an attempt to repel the alien-like figure from my bedside. In my attempt to wrangle my phone out of the bedding, I wrenched the I.V. inserted into my arm, again sending a shooting pain up the side of my arm. No matter, I thought, the human experiments department had showed up and I needed help ASAP.

I told Kevin, the duty officer, about the situation. I hadn’t been told, since arriving, if or when I’d be released. I also hadn’t been shown a bathroom or given food in the now nine-plus hours since I arrived at the airport. This time, I could tell that levers were moving because the attending physician at the hospital, who spoke perfect English, showed up at the door to my confines. To my surprise, she wasn’t wearing any space suit or protective equipment besides a typical surgeons mask. She was young, maybe in her early 30s, and reminded me of one of my friends back home from Ecuador, speaking softly and sweetly.

“I’m sorry that there hasn’t been much communication since you’ve arrived here,” she started out saying. “Please understand, we are being required to complete several tests here to insure that you don’t have coronavirus.”

“You must understand, I am asymptomatic,” I said. “I haven’t had a fever since I arrived here.”

“Unfortunately we are required to use an abundance of caution,” she said. “Please, allow us to complete these tests. If they testing comes back negative, you will be allowed to go from here.”

She said the testing process would take four to five hours.

That interaction proved to be a turning point in my stay, but that didn’t mean things wouldn’t get weirder. I subjected myself to the open-room X-ray (I’d heard a little ionizing radiation can be good for the immune system, anyway). Someone brought me a Gatorade, a sandwich and a cup to pee in.

My isolation unit at Hospital Pablo Arturo Suarez.

I managed to unhook myself from the EKG machine at one point and pee in my cup, dumping it out in the small sink in the corner of the room. At one point I inadvertently stepped in a sticky red liquid that was on the floor. Staring at the liquid, I thought, if I wasn’t sick before then surely I would return home with an exotic illness of the world. After digging in my bag to retrieve my sleep mask, I settled into the exceedingly uncomfortable military-style hospital bed, lulled by the pulsing IV in my arm and the buzzing of the single florescent light above.

An hour or so later I was surprised to watch a completely normally clothed person enter my room with a clipboard, without so much as a protective mask. Entirely in Spanish she attempted to interview my about my journey to Ecuador.

At another point I awoke to realize that the noises I had heard from neighboring spaces had stopped. There were no more beeps echoing in the hallway. Was everyone gone? It turned out that, in fact, everyone was gone. The ministry of public health decided overnight to evacuate the entirety of the hospital. I could smell the scent of freshly administered chlorine bleach. I checked the time, 3:45 a.m., and rolled painfully onto my other side before drifting back into uneasy sleep.

Morning

Waking up foggily in the hospital.

I woke up four hours later again needing to use the bathroom. The door was locked. I felt increasingly resigned to the competence of the Ecuadorian public health service when, around 9 a.m., a young man entered the room, again wearing terrifyingly alien protective clothing. He reattached the EKG wiring that I’d removed during my venture to the sink and asked if I’d like some breakfast. Finally, I thought, some service.

The EKG read 37 degrees Celsius. Still no fever. Heart rate normal. But it didn’t matter. I was still stuck in a room with peeling plaster, a barred window and sticky dried fluids on the floor.

“Que pasa con el examination?,” I attempted to ask about the status of my supposed test for COVID-19.

He responded that the coronavirus test would be processed during the day.

“El dottor fue decir que esso completar en solo quatro o cinco horas,” I responded that the doctor said the test would be done overnight. He shrugged. Great, I thought. No-one knows if there’s a test or when it would be processed. It again occurred to me just how lost I might be. I had read online that coronavirus tests in the United States were taking as long as four days to return results. Did Ecuador even have access to test kits yet? The whole thing felt increasingly shaky.

I messaged my friend in town: “Please come get me out of here. Just come.”

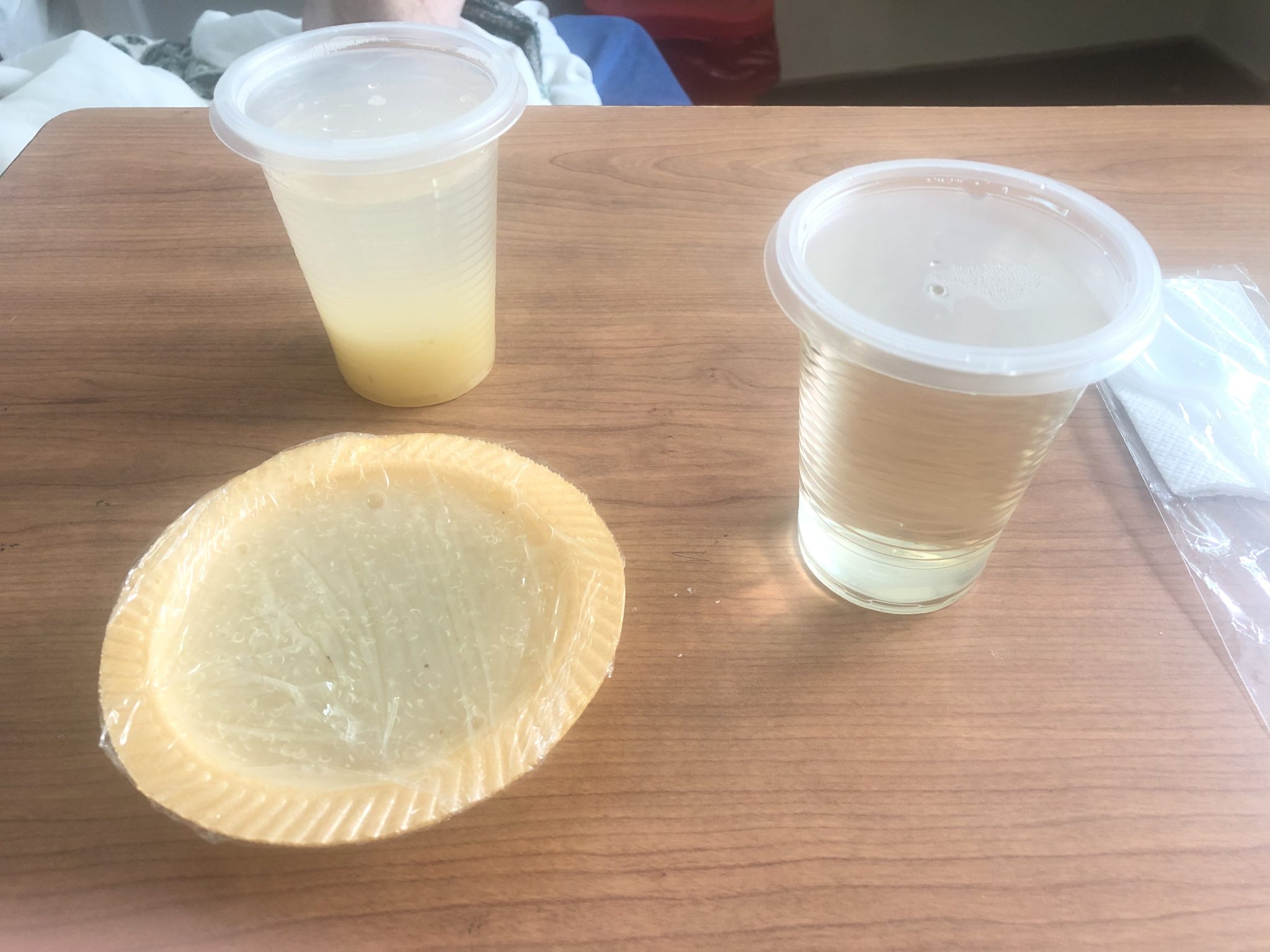

The young nurse returned with breakfast about an hour later. It consisted of a cup of red liquid, a cup of yellow liquid, and a paper bowl with what looked like quinoa soaked in applesauce.

My breakfast.

“Gracias.”

I wasn’t sure how relieved I should be at the breakfast laid out before me. I was not relieved at the messages I was getting from the outside. Joseph said the gates to the compound had been closed, a guard refusing entry to anyone not wearing space gear.

“I think your Government might be the only ones who can get you out,” he wrote.

Just then, my phone rang. The number registered ‘Washington, D.C.’ This time a different voice was on the phone. The man introduced himself as one of the diplomatic staff at the Embassy.

“We heard that you were in the hospital, and we are planning on visiting you this morning,” the man said.

I told him that my friend had attempted to see me and was disallowed.

“Yes, actually, we were told the same thing. Apparently, because you are there they have evacuated the entire hospital. They said we would not be allowed in to see you.”

My heart sank. I told the man about the situation with the bathroom. I told him I’d just been given a meal for the first time in 18 hours. He was receptive. The man said he would contact the head of the hospital on my behalf. He hung up the phone and I sank my head back down into the pillow.

The next 30 minutes felt like hours. It became increasingly uncertain whether anyone had an idea about when I might be released. At some point another masked health worker came in to ask the same questions.

“Why are you here? Where are you from? Do you have any symptoms?”

This individual, perhaps lacking awareness or instructions, led me from my bed and to the hall bathroom. It was the first bathroom I’d seen in 24 hours.

Back in bed, phone rang again.

“John, I’ve talked with the head physician at the hospital where you’re staying and expressed my concern over the situation involving the bathroom,” he said. “He said that, that’s right, you won’t be able to leave and use the bathroom but that they would bring some sort of bathroom to you.”

“Well, it’s good to know someone is in charge,” I said. “I just got back from the bathroom.”

We both laughed.

“I’ve been told that they have submitted your sample for testing, and that they are expecting the result sometime around 2 p.m.,” he said. “At that time, if your coronavirus test returns negative – which I fully expect it will as I’m sure you do – you will be released from the hospital like an ordinary patient. If the coronavirus test isn’t negative, well, we will cross that bridge when we have to.”

I thanked him at least three times and hung up the phone. I was again alone in the emergency ward, but some sense of ease had returned. My back ached and my body, unshowered since before I boarded the red-eye flight two days earlier, felt putrid.

With at least a semblance of reassuring news, I dialed my parents and told them what was happening. It was hard not to feel resigned to fate.

Alone

After an hour or so passed what sounded like a backup generator started moaning outside the window. Sure enough, yellow fumes started to roll off the top of the ceiling. I again called out for help, but there was not a sound to respond in the building. Maybe this is how I’ll go, I thought, suffocated on diesel fumes in a hospital. I started coughing – for the first time since I landed in the country – and tried to focus on breathing as little as possible. I fell back asleep for who knows how many minutes. The generator stopped by the time I regained awareness. Thank goodness, clean air.

Without entertainment or company, the next two hours stretched into eternity. My arm throbbed in pain. I could feel every drop of IV fluid hitting the inside of my artery like sand ticking through an hourglass.

At least I’m not in an Ecuadorian prison, I thought to myself, like in one of those TV dramatizations in which friends and family all presume the trapped soul has been kidnapped. At least my Embassy answered my call. How lucky must I be if this is the worst thing that has happened to me while travelling.

Then I looked around the room at the bare walls and barred window. What if I am in prison? Would it really be so different?

My mind ran through all the things that could possibly have gone wrong on my trip that didn’t; the pickpocket that never got to me at Carnaval, the robbery that didn’t happen, the Yellow Fever infection that I’d averted.

In anticipation of my release I felt a strange sense of gratitude. Maybe my masked caretakers were looking out for me after all.

Then I thought of the other patients in the hospital. Where had they gone? Were they still receiving treatment? I couldn’t stop seeing the wide-eyed faces of the people who had peered into my cell-like infirmary the day before, looking absolutely terrified yet unable to avert their eyes, as if I were some sort of extraterrestrial arrival. I wondered if I’d made that day’s news in Ecuador.

This is what fear does, I thought. It was as if the world around me had been distorted in some mirror. Me, the seemingly healthy American, now an object of terror. The sick and suffering, forgotten. It occurred to me then that this was perhaps the first time I’d been the subject of true fear. This was not like motherly fear, an only slightly irrational worry of some ridiculously unlikely but plausible horror befalling me on my way to a friend’s house at night. This was not jealous fear, the type that a prying partner exerts when they see a stranger’s number on a phone, some self-preservation precaution. This was something different entirely, a force of humanity I had not yet grasped or even understood existed.

There had been one case of COVID-19 in the entire nation, maybe a handful on an entire continent, and suddenly hundreds of sick people had been jostled from their hospital beds in the middle of the night and sent who knows where, all because of my presence. I didn’t even have symptoms when I arrived.

This fear, the fear I saw in the eyes of those terrified hospital workers, was a total distortion field. This is the force that makes people see others as less than human, I thought. This is the force that put kids back home in prison for selling a few grams of marijuana. This is the fear that stones witches to death and rallies the masses around acts of mass genocide. The fear of the body as a malignant force, a vector for both disease and paranoia.

And here I was, sitting right in the middle of it.

Negativo

As noon approached, I had mentally prepared myself for another two hours, maybe longer, maybe even days. I hadn’t seen anyone since breakfast had arrived. I unhooked myself for another meeting with my pee cup.

Fifteen minutes later, when two women opened the door in plain clothes, I knew something had changed. All I heard in the rambling explanation that we delivered was “COVID-19, negativo.”

“Estoy negativo, verdad?”

“Si!” the nurse replied. She seemed more excited than I was.

It took two hours more to get out of the apocalyptically vacant compound, but those two hours passed like minutes. Walking around the entirety of the emergency ward felt suddenly luxurious.

The attending physician at the hospital was a young, fit, bearded man, perhaps in his late 30’s or early 40’s. I’ve never felt a more reassuring handshake. He looked me in the eye as he extended his grasp, as if to say ‘you’re still human.’

After pulling the mangled and twisted catheter out of my arm, and sopping up globs of blood that oozed out, the doctor brought me a giant plate of chicken and rice. There was a soup and even a slice of cake. A few minutes later the doctor left me a slip of paper for 20 paracetemol tablets, to be collected at the hospital’s pharmacy.

Walking out of the abandoned emergency ward through the sprawling brown and beige complex felt otherworldly. Around one corner, as I was searching for the bathroom, a security guard stopped me and asked who I was. Apparently he hadn’t gotten the message that suspect zero had been let out. He looked me up and down as if staring at some rare animal before walking me to the bathroom.

A few minutes later I approached the hospital’s main gate. On the other side, locked out, were at least 30 people. The public hospital wouldn’t let them inside. They were coughing, they looked sick, some desperate as they haggled with the security guard.

I couldn’t help think: was this some dystopian vision of the weeks and months to come?

Walking out, I crossed the street and got into an Uber. My negative coronavirus test in hand and, with such, was still on vacation.

The responses below are not provided or commissioned by the bank advertiser. Responses have not been reviewed, approved or otherwise endorsed by the bank advertiser. It is not the bank advertiser's responsibility to ensure all posts and/or questions are answered.

8 comments

Thanks for sharing this. Please post this in Spanish so it can be shared with South American media

There’s tons of people being forcefully isolated over just the fear of the virus, and often the bad isolation facilities are getting people sick.

Thank you for sharing your personal experience.

People sometimes think that such extreme experiences don’t really happen or that the reported experiences “don’t tell the whole story” and would never happen to them or anyone they know. But when this kind of thing happens to a person, the person experiencing it know it as real as it is.

Given the sensitivity of the nasopharyngeal RT-PCR test, in the US, we would require 2 negative swabs taken over 24 hours apart for persons under investigation. Your fever on arrival would definitely be an indication to screen, and you were probably one of the asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic individuals with SARS-CoV-2 . By continuing to travel, you were likely continuing to spread virus to hundreds of people and contributed to the current crisis in the US on your return to New York that we as a healthcare professionals are now risking our lives to mitigate.

The rest of your experience reads like an anglo-centric, entitled, over-dramatized recollection of events. “My back muscles spasm-ed violently in pain as I felt the metal spear surge into my cephalic vein. Moments later, I was nearly sedated when a cool rush of paracetamol was unleashed into my arm.” to describe a routine IV placement? Not to mention that IV paracetamol/acetaminophen is not a sedative. What you describe as an “open-room X-ray” is a common way to take portable films both in the US and abroad in order minimize contaminating radiology facilities for individuals who we suspect have SARS-CoV-2. It appears you were given 2 N95 masks during your overnight stay in Ecuador (unless you brought them with you) which many healthcare workers in the US don’t even have access to at this time, yet you seem to hate on the facilities and subpar breakfast.

I’d also like to point out that most countries have been able to test for SARS-CoV-2 since the genome was released in January. The issue with US testing was scale and volume; public health labs in the US are able to run the test (which only takes a few hours with standard RT-PCR machines) efficiently on small numbers of samples, but were never designed for large scale operations.

The other issues you had seem to be mostly from lack of communication, due mostly to the fact that you don’t speak the language of the country you’re visiting. Perhaps if you could’ve communicated your needs in Spanish, they could’ve brought in a commode or urinal (as you were under isolation before clearing out the wing). Either way, sounds like a once in a lifetime event (hopefully) given the pandemic conditions and glad it seemed to have been sorted out.

I do speak Spanish, and there were two tests that both returned negative. Thanks for your informed comment.

Also, to accuse me, who was tested and cleared both blood and swab diagnostics for the disease, of spreading the virus to other countries and contributing to the problem this nation is now in smacks of ignorance about the progression of our national political response. At the time I was travelling, there wasn’t so much as a CDC or State Department travel advisory issued to anyone traveling anywhere but China. Aircraft were operating full.

The predicament that New York City and the United States is now in lies at the feet of our political and health leaders, and at their feet exclusively.

Ecuador, a nation with a less than a third of our per-capita GDP, had the foresight to screen passengers coming in on international flights and to treat all passengers who were symptomatic. They were screened in public health facilities, free of charge, and were and are not being sent bills.

When I returned to the immigration hall at Atlanta Hartsfield Airport over a week after this happened, there wasn’t so much as a thermometer in the entire building. Meanwhile, our medical institutions are sending patients who were caught on cruise ships bills that extend into 7 figures.

The risky situation that you and healthcare professionals are now in is a product of decisions that were made by this nation, in this nation exclusively.

That message is the intent and tone of this article.

Anglo-centric? I’m not from England.

This was a very intriguing read – in a horrifying way. Thank you for sharing your tale. Much respect for what you went through.

Your article was excellent. Thank you for sharing it.

Stranded in Asia when the crap hit the fan in March, your experience of being subjected to an unfamiliar healthcare system was my biggest fear. Transiting in Taipei, I was paged at the gate and my boarding passes were taken back and destroyed. All I could understand thru the masks and heavily accented english were the words “not possible to travel”. (Temperature checks had just been completed several times in the airport). So- I envisioned entering the Taiwanese healthcare system instead of the plane to Canada.

As it turned out, the monitor at my assigned seat on the plane was broken, and it was “not possible” for me to travel in that seat!

Great story